2023第45卷第8期

一直以来,创造力(creativity)都被视为有利于个人和组织发展的积极因素。相关学者对创造力的概念内涵、测量方法以及预测变量等进行了大量研究,极大地提升了我们对“什么是创造力”以及“什么能带来创造力”这两个科学问题的认识(综述如:Anderson等,2014)。这类以创造力为结果变量的研究数量庞大,但却无法帮助我们了解“创造力会带来什么”这一同样重要的现实问题。既往研究之所以更关心创造力的内涵及前因,是因为创造力被普遍认为是好的(Janssen等,2004;Khessina等,2018)。然而“创造力可以带来积极后果”这一隐含假设是否得到了充分的实证支持?创造力真的有益吗?有无副作用?对创造力后果的讨论关系着我们对创造力本质的理解以及对其社会影响的全面认识。

关于创造力后果研究的正式呼吁始见于Journal of Organizational Behavior一期特刊的介绍。特刊编辑Janssen等人(2004,p.130)指出:“根据创造力的定义,个体或团体从事创造性活动的目的是从中获益。然而创造力产生的过程是不可预测的、有争议的、竞争有限资源的。因此,尽管创造性活动的初衷是产生收益,但这类冒险的行为也可能给创新者带来意想不到的代价。”在Janssen等人的呼吁下,创造力的后果研究开始得到越来越多的学术关注。美国管理学会年会分别于2014年和2019年召开了两届专题研讨会,组织相关学者共同探讨创造力可能产生的后果及其干预手段(Harrison等,2014;Carnevale等,2019)。相关学者越来越清醒地认识到,人类的创造力既可以解决问题,也可能制造问题。尽管创造力的后果问题开始得到越来越多研究的关注,但相关实证探索大多视角分散,尚未形成对创造力双刃剑效应的全面刻画,尤其缺乏统一的理论视角对这一效应进行深入解读。

为了系统地分析创造力双刃剑效应的表现及内在机制,本文首先对相关实证研究进行了统计和归纳,发现当前对创造力后果的研究主要集中于绩效、健康、道德以及人际关系四大议题。在不同议题上,现有研究都得出了利弊共存的矛盾结果:创造力既可能带来高绩效,也可能导致低绩效;创造力既有利于个体健康,也可能损害健康;有创造力的人既可能展现美德,也可能更不道德;创造力既容易增加人际吸引,也可能招致人际排斥。我们认为这些“看似不合逻辑的发现”即管理学中所谓的悖论(Lewis,2000),因此本文尝试通过悖论理论(paradox theory)(Lewis,2000;Smith和Lewis,2011)来对创造力的双刃剑效应进行深入分析。悖论通常由一组“相互矛盾且相互关联的要素”构成(Lewis,2000;庞大龙等,2017),这些要素尤其是要素之间的张力(tensions)可以帮助我们聚焦复杂现象背后的本质问题。创造力作为一种复杂的社会心理现象,其本身也蕴含着“一连串的悖论”(a bundle of paradoxes)(Cropley,1997;Bledow等,2009;Miron-Spektor和Erez,2017)。我们认为,识别这些悖论要素、分析要素之间的张力是理解创造力双刃剑效应的关键。悖论理论指出,复杂现象中的悖论总体而言可以分为四类:学习、组织、执行以及归属(Smith和Lewis,2011;Schad等,2016)。据此,我们提出了创造力的学习、组织、执行以及归属悖论,以分别解释创造力在绩效、健康、道德和人际关系四个方面的双刃剑效应。

本文旨在为创造力研究领域做出如下贡献:第一,本文系统收集并梳理了有关创造力后果的实证研究,提炼出其对绩效、健康、道德以及人际关系的双刃剑作用,并总结了现有研究已经指出的中介机制和边界条件,为后续关于创造力后果的研究提供了较为全面的文献基础。第二,本文根据悖论理论对创造力的双刃剑效应进行了深入解读,提出了创造力的学习悖论、组织悖论、执行悖论以及归属悖论,并具体分析了其内涵,提出了相应的实践启示。通过悖论视角的透视,本文为理解创造力的双刃剑效应提供了一个全面、整合的视角,同时也为未来有关创造力后果的研究提供了新的议题与思路。

二、概念界定及文献检索过程一直以来,创造力作为一种重要且复杂的现象吸引了各个学科学者的注意。不同取向的学者对创造力的定义不尽相同。本文参照Runco(2004)的4Ps(person,process,press,product)模型,将创造力定义为个体水平上与创意生产相关的社会心理现象(Batey,2012;Rhodes,1961)。在管理研究领域,与创造力(creativity)密切相关的另一个概念是创新(innovation)。创造力是创新“模糊的前端”,二者关键的区别在于研究层次和主体:微观层面,聚焦于个体或团队创意生产的概念常称为创造力;而宏观层面,聚焦于创意生产之后的创意执行、市场化等涉及更多、更广泛主体的概念,常称为创新(Amabile和Pratt,2016)。以二者的后果研究为例,有关创造力后果的研究通常关注微观层面的结果变量,如个体的工作绩效、心理健康、人际关系等等;而有关创新后果的研究则更多讨论其对企业盈利能力、投资者评价、国家竞争力等中宏观结果变量的影响(如:Damanpour和Evan,1984;Henderson和Clark,1990)。由于创造力对企业绩效和竞争优势的重要影响,在心理学和组织行为学领域,大量实证研究探讨了提升员工创造力的因素(综述如:Anderson等,2014)。然而,正如前文所述,“这类冒险的行为也可能给创新者带来意想不到的代价”(Janssen等,2004),因此,本文基于心理学和组织行为学研究,尝试从微观层面探讨创造力的后果。

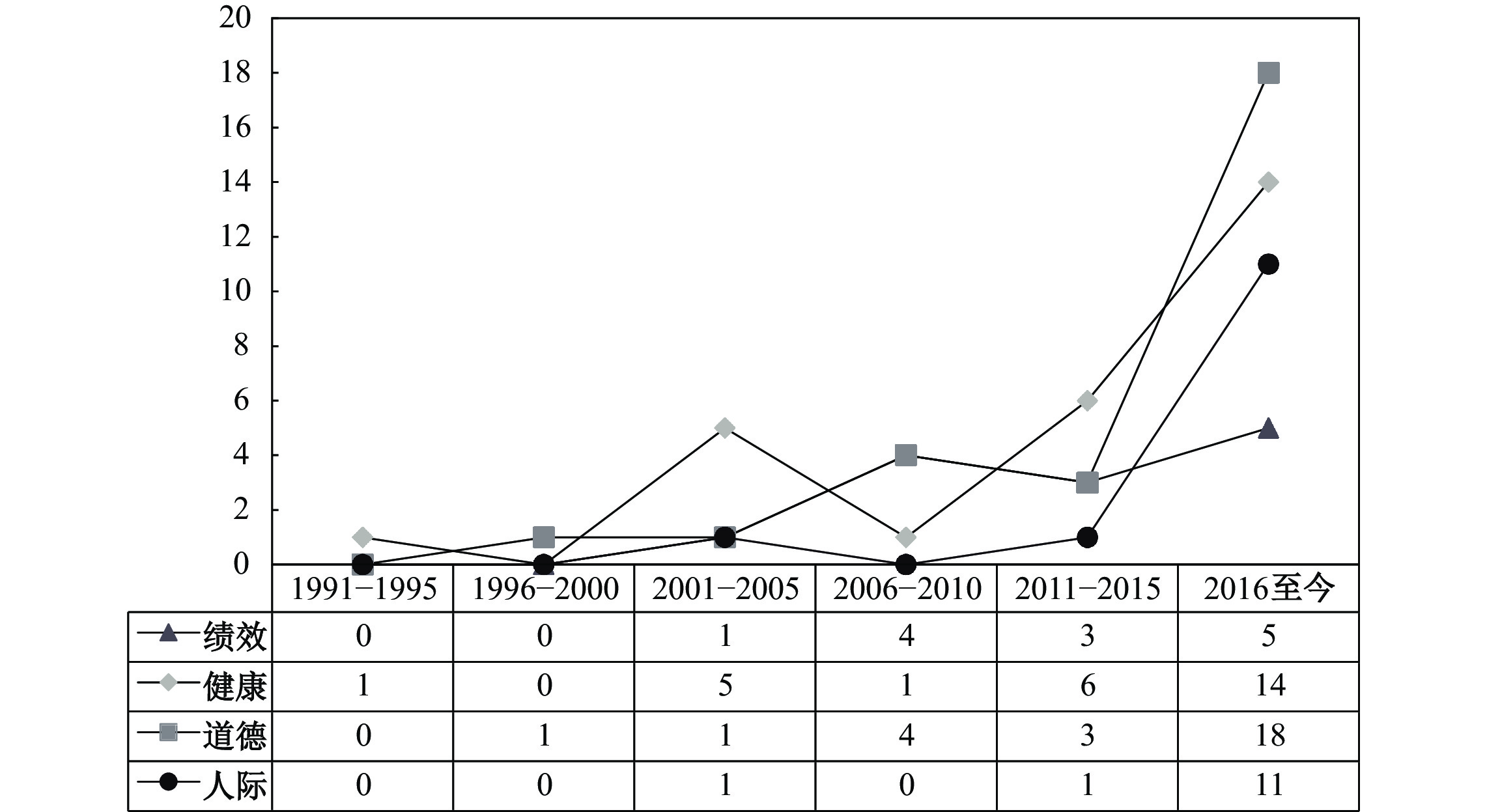

截至2022年2月,以 “creativity”和“consequence”为检索词在Web of Science、ProQuest,工业与组织管理学会(SIOP)以及美国管理学会年会(AOM)可以检索到1042篇文献。以社会科学为研究领域,英语和汉语为语种进行筛选后剩余668篇。对初步检索到的文献根据以下标准进行筛选:(1)发表领域为心理学、管理学或组织行为学;(2)研究层次为个体;(3)研究模型中把创造力当作自变量而非因变量;(4)研究对象为成年人。最终筛选出目标文献80篇。我们将搜集到的文献按照关键词进行主题归纳,结果发现现存关于创造力后果的研究主要聚焦于绩效(13篇)、健康(27篇)、道德(27篇)以及人际关系(13篇)这四个主题,并且每个主题下的研究都体现出了创造力的双刃剑效应。对这些文献的发表情况进行统计发现,关于创造力后果的研究数量在最近十年增长较快(参见图1)。接下来,本文将以悖论理论为框架,对创造力在每一主题下的双刃剑效应进行深入解读。

|

| 图 1 创造力的后果相关研究发表情况(1991年至今) |

所谓“学习悖论”(learning paradox)指的是个体既要“利用”,又要“探索”,但这两种活动此消彼长,很难平衡(Smith和Lewis,2011)。“利用”指的是精炼已有信息、改良现有技术等较为保守的学习方式;而“探索”指的是搜集新异信息、开展实验试错等较为冒险的学习方式。既往针对学习悖论的研究发现,“利用”往往可以保证短期绩效,但却容易使个体陷入“成功陷阱”,进而妨碍未来发展。相反,“探索”虽然可能带来价值巨大的未来绩效,但试错受挫的过程也容易使个体陷入“失败陷阱”,进而牺牲短期绩效(He和Wong,2004)。理想情况下,保持“利用”和“探索”两种活动之间的平衡,便可以保证长久、良好的绩效表现。然而现实生活中,创新者囿于有限的内外部资源,往往很难保证两种活动并行不悖。

由于学习悖论难以克服,以往研究确实更常发现创造力对个体绩效的消极影响。譬如,Zhang和Bartol(2010)基于注意力能力理论(attention capacity theory)提出,个体的注意力资源是有限的,将有限的注意力适度投入创造性活动或能提高绩效表现,但过度投入则会妨碍其他活动,进而损害整体绩效。他们针对信息技术行业从业者的调查发现,员工的创造力过程投入与其整体工作绩效呈倒U形关系,并且这一关系受到员工工作经验的调节。经验丰富者更能平衡不同的任务要求,合理分配自己的注意力资源,因此更少耽误整体绩效。在“利用”和“探索”间灵活切换并非易事,一些研究基于自我调节理论(self-regulation theory)指出,创新者往往容易产生失调性坚持(dysfunctional persistence),即对某一项或某一阶段的任务太过投入,进而妨碍其在不同任务间转换的能力,最终累及整体绩效(Fischer和Hommel,2012;Li等,2020;Miron等,2004)。Bayus(2013)提出了创新者的认知固化(cognitive fixation)倾向,即创造力水平高的个体往往容易沉溺于对既往成功经验的利用,丧失探索新知识的动力或能力,从而损害长期绩效表现。相关研究同时指出,鼓励探索的组织规范,或积极的跨界合作,可以削弱认知固化的消极效应(Miron等,2004;Audia和Goncalo,2007;Arts和Fleming,2018)。

少数研究曾发现创造力对个体绩效的积极作用。譬如相关研究曾在大学生(Chamorro-Premuzic,2006)、大学教师(Davidovitch和Milgram,2006)以及公司员工(Zhang等,2020;Sarooghi等,2015;Harari等,2016)身上发现,更高的创造力可以带来更好的绩效表现。遗憾的是这些研究较少探究创造力有利于个体绩效的内在机制和边界条件。仅有Wronska等(2018)指出,二者之间呈正相关关系可能是因为创造力水平高的个体注意幅度(breadth of attention)更广。更广的注意幅度有助于创新者收集不同信息,探索新的方法,以实现更好的绩效表现。

总体来看,关于创造力–绩效消极关系的研究大多采用了资源或者资源调节相关理论,如注意力能力理论、自我调节理论。这些研究之所以提出创造力对绩效的消极作用,可能正是因为资源视角能更好地捕捉个体面临的学习悖论。相反,关于创造力–绩效积极关系的研究缺乏清晰的理论视角。这些研究大多采用实验室中的简单任务(如:Wronska等,2018)、横截面问卷(如:Davidovitch和Milgram,2006;Zhang等,2020),或对绩效采用短期、单一的定义与测量(如:Sarooghi等,2015;Harari等,2016)。之所以发现创造力有利于绩效,很可能是因为这些研究缺乏系统的理论指导,研究设计也相对简单,因而更难捕捉到“利用”与“探索”之间的张力,研究发现较为片面。

四、组织悖论及创造力对个体健康的影响所谓“组织悖论”(organizing paradox)指的是个体既要“自主”,又受“控制”,但这两种要求相互矛盾,很难平衡(Smith和Lewis,2011)。“自主”指的是个体决定其所从事活动的内容、方式、节奏等的自由裁量权。“控制”指的是个体从事创造性活动时所面临的外部限制,譬如组织规定的创作目标、内容、执行方式、截止日期等等。相关研究发现,虽然自主性有利于个体表达创造力,但过度自主导致的放纵也可能妨碍身心健康(Liu等,2011)。同样的,组织控制虽然容易使员工感觉有压力,但却更能保证创造性活动的生产效率(Byron等,2010)。理想情况下,对创新者赋予适度的“自主”并进行适度的“控制”最有利于其健康、可持续的发展。然而现实生活中,不论创新者个人还是组织者都很难做到张弛有度。

由于组织悖论难以克服,既往研究确实发现创造力对个体健康会产生消极影响。首先,过于严苛的“控制”确实会导致员工出现严重的压力反应(Amabile等,2002),并且这种消极影响在员工感觉不公平的情况下尤其严重(Janssen,2004)。Vuori和Huy(2016)以情绪为视角的研究指出,创造性的工作任务更可能使个体在持续的紧张和反复的试错中体验到对不确定性的恐惧感。Eun和Chua(2020)基于个人–组织匹配理论提出,创造力之所以容易令员工感觉耗竭,是因为创造力要求降低了个体感知到的个人–组织匹配性,并且由于这种不适配感知而产生的耗竭感在女性员工身上尤其严重。Ng和Wang(2019)则基于社会比较和心理摆脱理论指出,哪怕只是看到同事展现出创造性行为也会对员工产生心理压迫,进而导致其在下班后难以实现心理摆脱,出现失眠、敌意等压力症状,并且这种效应对主动性人格的员工而言尤其严重。其次,无节制的“自主”也可能导致个体健康受损。譬如Krause等(2019)基于资源保存理论研究发现,从事创造性活动会导致个体自我放纵,进而做出更多不利于身体健康的选择,譬如进食更多的垃圾食品、过度饮酒以及更少锻炼。Katz(2020)基于反事实思维理论提出,创造性思维容易引发反事实上行比较(upward counterfactuals),从而导致个体对现状更加不满。

也有部分研究曾指出创造力对个体健康的积极作用。譬如心流理论认为,创造性活动常常需要个体全神贯注地工作,在专注于工作的过程中个体常常能体会到高度的兴奋与充实感,这种心流体验(flow experience)即是创造力的内在奖励(Csikszentmihalyi等,2018)。根据具身认知理论(embodied cognition theory)(Niedenthal等,2005)的解释,创造力本身包含的“解放”隐喻可以有效缓解心理压力,Goncalo等人(2015)将这一现象命名为创造力的 “解放效应”(liberatingeffect)。事实上,相关研究早就发现,从事创造性活动可以宣泄精神、缓解痛苦(McNiff,2004)。譬如写作(施铁如,2006)、绘画(陶晶和伍莉莉,2011)、音乐(沈靖,2003)等创造性活动都可以帮助个体从负面事件中转移注意力,通过自主的自我表达(autonomous self-expression)释放压力,促进创伤后的成长,甚至重建生命的意义(Leckey,2011;Kapoor和Kaufman,2020;Goncalo和Katz,2020;Chiu等,2019;Conner等,2018;Bujacz等,2016;Caddy等,2012;Brunyé等,2013;Feist,1994),并且这一效应可能对处于集体主义文化中的个体尤其明显(Tang等,2021)。Helzer和Kim(2019)以及Jamison(2019)基于压力的认知评估模型指出,创造力可以减少工作压力和倦怠,这是因为创造力水平高的个体对压力源有更多元的认知解读,并且这一积极效应在组织承诺水平高的员工身上更加明显。更进一步,当个体运用创造力解决了问题,尤其是进一步收获了他人的认可和赞许时,他们往往会产生更强的自我效能感(Forgeard,2015),以及愉快、骄傲、释然、满意等积极情感(Amabile等,2005),进而有利于其保持健康的身心状态。

总体来看,创造力对个体健康的双刃剑效应主要源自“自主–控制”这一组织悖论。提出创造力–健康消极关系的研究大多聚焦于“控制”场景,如与领导、同事交互过程的期望压力,社会比较等等。此时创新者受到组织控制的影响,因而更容易表现出恐惧、耗竭等压力反应。反之,提出创造力–健康积极关系的研究则大多发生在“自主”场景,譬如自由创作和艺术疗愈场景,创新者可以从自身需求和偏好出发,自主进行创造性活动,因而会更多地感受到心流体验和解放效应。

五、执行悖论及创造力对个体道德的影响所谓“执行悖论”(performing paradox)指的是个体既要“灵活”,又不能太灵活以至于失去“约束”,这两种要求相互矛盾,很难实现平衡。创新者的特点是思维灵活,勇于打破常规,可一旦其对常规的挑战超越了伦理准则就难免导致不道德行为。富有创造力的个体认知灵活性高,但这种灵活作为手段,可以执行于不同的目标。一个富有创造力的人可以将聪明才智用于帮助他人,也可以将其用于自我开脱甚至违法乱纪,不同的执行方向决定了创造力导致的不同道德后果。理想情况下,一个“从心所欲不逾矩”的创新者既要具备打破常规的灵活,又要能够及时约束自己超出道德规范的行为,这实际上对个体提出了更高甚至相左的要求。

由于执行悖论难以克服,现有大量研究指出了创造力对道德的消极作用。譬如,富有创造力的人更容易撒谎(Gino和Ariely,2012;Walczyk等,2008;Storme等,2021),更不正直(Beaussart等,2013),更多违法(Lebuda等,2021)、辱虐(Qin等,2020)以及破坏环境(Qin等,2022)的行为。道德推脱(moral disengagement)是创造力导致不道德行为的关键机制,富有创造力的人认知灵活性更强,因此更善于为自己的不道德行为开脱(Mai等,2015;Keem等,2018;Qin等,2020;Zheng等,2019),这种为自身不道德行为辩护的倾向在个体道德认同水平更低(Keem等,2018)、换位思考能力更差(Hui等,2022)、特质性道德推脱水平更高(Umphress等,2020;Qin等,2022),或在道德标准更模糊的环境下(Gutworth和Hunter,2017)尤其强烈。此外,由于创造力经常被视为一种宝贵且稀缺的能力,因此创造力水平高的个体往往表现出较强的心理特权感(psychological entitlement),这种特权感在创造力稀缺(Vincent和Kouchaki,2016)、绩效压力大(Mai等,2022),以及奖励不足(Ng和Yam,2019)的情况下尤其强烈,因此更容易导致偏差行为。最近,Ming和Bai(2021)基于自我损耗理论提出,创造力过程投入会导致个体的自我损耗,因而导致更多不道德行为,好在支持创造力的环境可以为个体补充资源,从而缓解这一效应。

那些足够灵活,又能够进行自我约束的创新者,反而会展现更多的美德。来自名人传记的证据显示,连续突破性创新者通常都志存高远、恪守美德。譬如,著名的发明家富兰克林曾经为自己制定了十三条道德戒律,要求自己每周专注于掌握其中一种。再如,居里夫人为了推动科学的自由发展而没有为镭的提纯工艺申请个人专利;她第一次获得诺贝尔奖的奖金也大多分给了周围的家人、朋友以及研究伙伴(Schilling,2018)。除了这些名人轶事,研究也曾发现创造力水平高的人更有道德(Shen等,2019;Teal和Carroll,1999;Buchholz和Rosenthal,2005;Weitzel等,2010;Ścigała等,2020),这些人不仅具备灵活发散的思维,同时还具备较高的道德理想主义水平(Bierly Ⅲ等,2009)、道德决策能力(Mumford等,2010)以及印象管理动机(Carnevale等,2021)。Xu等(2022)的一系列研究发现,创造力水平高的人更可能捐款,甚至只是短暂参与创造性任务也会显著促进个体的捐款行为,这是因为创造力可以激发个体的积极情感。Zhou等(2022)发现,相比为自己牟利,具有创造性人格的人甚至在会造福他人的任务中表现得更加积极,这可能是因为他们更相信自己具备帮助他人的能力。

总体而言,创造力对个体道德的双刃剑效应体现出了“灵活–约束”这一执行悖论。主张创造力–道德消极关系的研究较多关注“灵活”元素,譬如采用“道德推脱”等理论视角,强调创新者将认知灵活的优势用于自我辩护的可能。反之,主张创造力–道德积极关系的研究则更多聚焦于“约束”因素,譬如创新者更高的道德水平或更强的印象管理动机都可以帮助其进行自我约束,将聪明才智用于行善而非作恶。

六、归属悖论及创造力对人际关系的影响所谓“归属悖论”(belonging paradox)指的是创新者既要“求同”,又要“存异”,两种归属取向相互矛盾,很难达到平衡(Brewer,1991)。“求同”意味着服从集体,保持与大多数人相一致,这样最有利于融洽的人际关系,但一个被群体同化的人很难产生与众不同的创意。相反,“存异”保证了个体萌生新颖想法的可能,然而当一个特立独行的异类往往会招致他人的排斥甚至攻讦。理想情况下,保持“和而不同”便可以使个体在发挥创意的同时保持良好的人际关系。然而现实中,这是很难达到的完美状态。

因为归属悖论很难克服,既往研究大多发现了个体创造力对其人际关系的消极作用。譬如,富有创造力的员工更可能招致同事的孤立和排斥,因为他们往往更容易得到组织的资源优待(Breidenthal等,2020),被视为规则的破坏者(Keem等,2019),因而引起同事的嫉妒(Mao等,2021),并进一步升级为人际冲突(Janssen,2003;Zhang等,2018)。这种由社会比较而形成的人际惩罚,对于本职工作表现差(Dadaboyev等,2021)、不善社交(Zhang等,2016;Keem等,2019;Li,2020;Mao等,2021),或工作投入水平高(Janssen,2003)的员工而言更加严重。Mueller等(2011)发现创造力水平高的员工更不可能被选拔为领导,因为大众心目中的领导往往是控制不确定性的人,而创新者常常会引发不确定性。创造力水平高的员工也可能引起领导的排斥,相比掌握目标导向,绩效目标导向的领导更容易将员工的创造性行为视作对其领导方式的挑战和工作能力的质疑(Zhang等,2018)。从事创造性活动也可能影响家庭关系。Harrison和Wagner(2016)的研究指出,员工从事创造性活动会显著减少其与伴侣共处的时间。

目前关于创造力对人际关系积极影响的实证研究几乎没有。有限的研究指出,个体表达创意的过程也是在向他人展示更多的内在自我,而这种自我表露有可能会有利于建立更亲密的人际关系(Goncalo和Katz,2020)。创造是漫长而艰苦的活动,因此共同创造的经历有可能会降低个体的孤独感,增加归属感(Rouse,2020)。虽然缺乏相应的实证支持,但Goncalo等(2021)在最近的理论文章中提出了创造力有利于发展人际关系的观点。他们认为不论是生产还是执行创意,个体都难免要借助外界的力量,寻求灵感或者合作,这个过程有可能增加个体的社会联结。至于这种社会联结能否带来积极的人际体验,则有可能跟创意的具体内容以及社会交往的其他细节有关。

创造力对人际关系的双刃剑作用在很大程度上体现了“求同–存异”这一对归属悖论。主张创造力–人际关系消极作用的研究主要基于社会比较、人际排斥等理论揭示了创新者为了“存异”而难以“求同”的尴尬处境。现有有关创造力–人际关系积极影响的实证研究相对稀少,这也显示了归属悖论的克服难度,未来的研究可以重点关注这一研究缺口。

七、总结与未来研究展望通过对现有研究的系统梳理本文发现,当前对创造力后果的研究主要集中于绩效、健康、道德以及人际关系四个主题,并且在不同主题上都得出了利弊共存的矛盾结论(详见表1)。为了深入理解创造力的双刃剑效应,本文在文献梳理的基础上结合悖论理论提出了创造力的学习悖论、组织悖论、执行悖论以及归属悖论。我们发现,创造力的后果之所以表现出这种双刃剑效应,是因为:(1)学习/组织/执行/归属悖论天然难以克服,因而捕捉到悖论张力的研究常常会发现平衡失败的现象,也即创造力的消极后果;(2)一些提出创造力积极作用的研究部分是因为找到了弥合悖论的策略(如,既“灵活”又可以通过印象管理手段自我“约束”的创新者往往展现出美德),部分是因为其研究设计相对简单,未能捕捉到悖论元素之间的张力(如,提出创造力–健康积极关系的研究大多针对自由创作、艺术疗愈等“自主”场景,没有考虑“控制”相关问题)。

| 结果主题 | 影响 | 中介机制 | 边界条件 | 相关研究 |

| 个体绩效 | 积极 | 注意幅度 | (几乎没有) | Chamorro-Premuzic(2006);Davidovitch和Milgram(2006);Sarooghi等(2015);Harari等(2016);Wronska等(2018);Zhang等(2020) |

| 消极 | 失调性坚持;低任务转换能力;认知固化 | 工作经验;跨界合作;鼓励探索的组织规范 | Miron等(2004);Audia和Goncalo(2007);Zhang和Bartol(2010);Fischer和Hommel(2012);Bayus(2013);Arts和Fleming(2018);Li等(2020) | |

| 个体健康 | 积极 | 心流体验;解放效应/自主表达;多元认知解读;自我效能感;积极情感 | 个体/集体主义文化;组织承诺 | Feist(1994);沈靖(2003);McNiff(2004);Amabile等(2005);施铁如(2006);Leckey (2011);陶晶和伍莉莉(2011);Caddy等(2012);Brunyé等(2013);Forgeard(2015);Goncalo等(2015);Bujacz等(2016);Csikszentmihalyi等(2018);Conner等(2018);Chiu等(2019);Helzer和Kim(2019);Jamison(2019);Goncalo等(2020);Kapoor和Kaufman(2020);Tang等(2021) |

| 消极 | 自我放纵;反事实上行比较;消极情绪如恐惧;个人–组织不匹配;心理摆脱困难 | 组织公平感;性别;主动性人格 | Amabile等(2002);Janssen(2004);Vuori和Huy(2016);Krause等(2019);Ng和Wang (2019);Eun和Chua(2020);Katz(2020) | |

| 个体道德 | 积极 | 积极情感;创造力声誉维持;创造力自我效能感 | (几乎没有) | Teal和Carroll(1999);Buchholz和Rosenthal (2005);Bierly Ⅲ等(2009);Mumford等(2010);Weitzel等(2010);Shen等(2019);Ścigała等(2020);Xu等(2022);Carnevale等(2021);Zhou等(2022) |

| 消极 | 道德推脱;心理特权;自我损耗 | 道德认同;换位思考;特质性道德推脱;道德标准凸显;创造力稀缺;绩效压力;奖励不足;组织创造力支持 | Walczyk等(2008);Gino和Ariely(2012);Beaussart等(2013);Mai等(2015);Vincent和Kouchaki(2016);Gutworth和Hunter(2017);Keem等(2018);Ng和Yam(2019);Zheng等(2019);Qin等(2020);Umphress等(2020);Qin等(2022);Hui等(2022);Lebuda等(2021);Mai等(2022);Ming和Bai(2021);Storme等(2021) | |

| 人际关系 | 积极 | 自我表露 | (几乎没有) | Goncalo和Katz(2020);Rouse(2020);Goncalo等(2021) |

| 消极 | 同事的嫉妒;领导威胁感知;与伴侣共处的时间 | 政治技巧;独狼倾向;领导–成员交换;角色内工作绩效;工作投入;领导掌握/

绩效目标导向 |

Janssen(2003);Mueller等(2011);Zhang等(2016);Harrison和Wagner(2016);Zhang等(2018);Keem等(2019);Breidenthal等(2020);Dadaboyev等(2021);Li (2020);Mao等(2021) |

通过悖论理论的透视我们发现,传统的线性思维并不适用于我们对创造力后果的理解。譬如,是否创造力水平越高,个体绩效表现就越好呢?当前的研究无法为这种问题提供直接的答案。同样,类似“创造力到底会导致更多道德还是不道德行为”这样非黑即白的提问也无法获得简单的解答。要使创造力带来长久、积极的绩效/健康/道德/人际关系后果,创新者和管理者必须要认识到创造力的悖论本质,采用“兼容并蓄”(both/and)的思考方式,追求悖论元素的对立统一。有鉴于此,我们对四种悖论视角下创造力的双刃剑效应进行了总结,并提供了相关实践启示(详见表2)。

| 悖论视角 | 悖论要素举例 | 要素极化的后果 | 实践启示 |

| 学习悖论 | 利用(exploitation) | 过度利用则损失长期绩效 | 创新者必须在利用和探索两种学习方式间取得平衡,如此才能保障可持续的、良好的绩效表现 |

| 探索(exploration) | 过度探索则损失短期绩效 | ||

| 组织悖论 | 控制(control) | 过度的控制导致恐惧和压力 | 管理者和创新者必须在自主和控制两种组织方式间取得平衡,如此才能保障创新者的健康水平 |

| 自主(autonomy) | 过度的自主导致自我放纵 | ||

| 执行悖论 | 约束(constraint) | 过度的约束会扼杀创意 | 创新者既要具备打破常规的灵活,又要能够及时约束自己超出道德规范的想法,如此才能带来道德的结果 |

| 灵活(flexibility) | 过度的灵活会突破道德规则 | ||

| 归属悖论 | 求同(assimilation) | 过度的合群会扼杀创意 | 创新者必须在求同和存异两种归属取向中取得平衡,如此才能保障良好的人际关系 |

| 存异(differentiation) | 过度追求独特会招致人际排斥 |

以下,本文将结合当前研究的不足对未来研究进行展望。第一,从文献数量上讲,当前对创造力后果的研究更多关注其阴暗面,譬如聚焦于创造力对绩效/道德/人际关系消极效应的研究的数量(7/17/10)普遍多于聚焦于相应积极效应的研究的数量(6/10/3)。这样的研究取向导致我们对创造力的积极效应缺乏足够的认识。譬如有关创造力–绩效积极效应的研究之所以数量不多,主要是由于既往研究通常默认创造力有益于绩效,甚至将创造力等同于绩效,但却缺乏对这种潜在假设的严谨检验(Khessina等,2018)。再如,有关创造力–人际关系的研究几乎没有直接检验过创造力对人际关系的积极影响,这种疏忽也是令人惊讶的。创新者不仅是规则挑战者,同时也是问题解决者、价值创造者,这样的人或许更可能成为社交网络的中心,或拥有更高质量的人际关系(Rouse,2020)。最后,“创新者更不道德”几乎成为创造力与道德关系的主流认知,然而这样的结论是否符合真实情况呢?主张这一假设的研究大多采用实验操纵的方法,实验环境中缺乏明显的道德准则,研究结论尚缺乏足够的外部效度(Gutworth和Hunter,2017)。而在真实组织情境中进行问卷调查的研究大多以自陈方式收集不道德行为,得出创新者更不道德的结论也可能恰恰是由于创新者不善或不屑掩饰的率真。未来的研究可以重新审视创造力的积极面,尤其是着力填补积极效应的机制空白。

第二,当前研究对创造力双刃剑效应的边界条件挖掘不足。譬如,关于创造力对绩效/道德/人际关系积极效应的研究几乎没有指明任何调节因素,这种缺失很可能会限制我们对创造力双刃剑效应的正确认识。未来的研究可以挖掘影响创造力双刃剑效应的调节因素。譬如,创造力的绩效、健康、道德以及人际关系后果都可能受到性别因素的调节。既往有关创造力性别差异的研究发现,大众观念里女性更不适合从事创新活动,因为人们经常将创造力与男性特征譬如大胆、独立,而非女性特征譬如合作、支持联系起来(Proudfoot等,2015;Proudfoot,2017)。不仅如此,女性从事创造性活动还存在独特的性别折扣效应(gender discount effect),即在同样的创新表现下,女性往往比男性收获更低的外部评价(Elmore和Luna-Lucero,2017;Hora等,2022;Luksyte等,2018)和更差的市场反应(Jensen等,2018)。根据性别的自我图式理论(Martin和Ruble,2010),在成长过程中内化了性别刻板印象的女性往往也会排斥创造性工作,避免因违反刻板印象而可能受到的惩罚。由此我们有理由猜测,相比男性,女性创新者可能经历更差的绩效评价、更多的健康损害、更少的道德偏差,以及更差的人际关系。

第三,当前对创造力双刃剑效应的研究更多停留在单一视角的描述层面,而较少探索调和悖论的个体策略。既往有关创新悖论的讨论及研究大多集中于公司层面(如:Lengnick-Hall,1992;Raisch等,2009;罗瑾琏等,2021),而实际上,越来越多的学者已经认识到,解决创新悖论的关键还是在于理解其微观基础,即创新者的感知和行为(罗瑾琏等,2018;Kauppila和Tempelaar,2016;Miron-Spektor等,2018;Schad等,2016)。近年来,越来越多的学者开始了这方面的探索。譬如有关创新者双元能力(individual ambidexterity)的研究发现,目标管理(Kauppila和Tempelaar,2016;Miron-Spektor和Beenen,2015;Miron-Spektor等,2022)、任务协同(Papachroni和Heracleous,2020)、角色分割(Tempelaar和Rosenkranz,2019;Wu和Yuan,2020)、社交网络管理(Rogan和Mors,2014)等策略都可以帮助个体缓解创造力悖论。目前,类似研究主要集中于“探索–利用”悖论,而很少关注其他种类悖论的调和策略。未来的研究可以从不同的理论视角挖掘其他悖论的具体表现并寻找相应策略。

第四,未来的研究可以从领导者的角度探索管理悖论的具体实践。譬如,近年来有关学者提出了悖论式领导行为(paradoxical leader behavior)概念,并刻画了领导者整合矛盾的具体行为,如保持短期效率与长期发展、保持组织灵活性与稳定性、关注股东与利益相关者等等(Zhang和Han,2019)。研究发现,悖论式领导可以更好地激发员工创造力(Shao等,2019;Zhang等,2022)。其他管理实践,譬如过程目标控制(Rosing等,2018)、精准激励(Giarratana等,2018;Sue-Chan和Hempel,2016)、双元领导(罗瑾琏等,2016;Zacher等,2016)、双重领导(Hunter等,2017)、团队重构(赵锴和向姝婷,2021)等手段也可以有效缓解创造力悖论。未来的研究可以继续寻找相应策略,为领导者管理创新悖论提供更加全面、科学的干预之道。

| [1] | 罗瑾琏, 管建世, 钟竞, 等. 迷雾中的抉择: 创新背景下企业管理者悖论应对策略与路径研究[J]. 管理世界, 2018, 34(11): 150–167. |

| [2] | 罗瑾琏, 胡文安, 钟竞. 双元领导对团队创新的影响机制研究——基于互动认知的视角[J]. 华东经济管理, 2016, 30(7): 35–44. |

| [3] | 罗瑾琏, 唐慧洁, 李树文, 等. 科创企业创新悖论及其应对效应研究[J]. 管理世界, 2021, 37(3): 105–122. |

| [4] | 庞大龙, 徐立国, 席酉民. 悖论管理的思想溯源、特征启示与未来前景[J]. 管理学报, 2017, 14(2): 168–175. |

| [5] | 沈靖. 音乐治疗及其相关心理学研究述评[J]. 心理科学, 2003, 26(1): 176–177. |

| [6] | 施铁如. 写作的心理治疗与辅导: 功能、原理及其应用[J]. 华南师范大学学报(社会科学版), 2006(1): 116–121,128. |

| [7] | 陶晶, 伍莉莉. 绘画创作对心理治疗的作用探微[J]. 西南大学学报(社会科学版), 2011, 37(4): 216–217. |

| [8] | 赵锴, 向姝婷. 如何解决团队创新悖论?基于成员认知风格“组型”与“构型”视角的探究[J]. 心理科学进展, 2021, 29(1): 1–18. |

| [9] | Amabile T M, Barsade S G, Mueller J S, et al. Affect and creativity at work[J]. Administrative Science Quarterly, 2005, 50(3): 367–403. |

| [10] | Amabile T M, Hadley C N, Kramer S J. Creativity under the gun[J]. Harvard Business Review, 2002, 80(8): 52–61,147. |

| [11] | Amabile T M, Pratt M G. The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning[J]. Research in Organizational Behavior, 2016, 36: 157–183. |

| [12] | Anderson N, Potočnik K, Zhou J. Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework[J]. Journal of Management, 2014, 40(5): 1297–1333. |

| [13] | Arts S, Fleming L. Paradise of novelty—or loss of human capital? Exploring new fields and inventive output[J]. Organization Science, 2018, 29(6): 1074–1092. |

| [14] | Audia P G, Goncalo J A. Past success and creativity over time: A study of inventors in the hard disk drive industry[J]. Management Science, 2007, 53(1): 1–15. |

| [15] | Batey M. The measurement of creativity: From definitional consensus to the introduction of a new heuristic framework[J]. Creativity Research Journal, 2012, 24(1): 55–65. |

| [16] | Bayus B L. Crowdsourcing new product ideas over time: An analysis of the dell IdeaStorm community[J]. Management Science, 2013, 59(1): 226–244. |

| [17] | Beaussart M L, Andrews C J, Kaufman J C. Creative liars: The relationship between creativity and integrity[J]. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 2013, 9: 129–134. |

| [18] | Bierly Ⅲ P E, Kolodinsky R W, Charette B J. Understanding the complex relationship between creativity and ethical ideologies[J]. Journal of Business Ethics, 2009, 86(1): 101–112. |

| [19] | Bledow R, Frese M, Anderson N, et al. A dialectic perspective on innovation: Conflicting demands, multiple pathways, and ambidexterity[J]. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2009, 2(3): 305–337. |

| [20] | Breidenthal A P, Liu D, Bai Y T, et al. The dark side of creativity: Coworker envy and ostracism as a response to employee creativity[J]. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 2020, 161: 242–254. |

| [21] | Brewer M B. The social self: On being the same and different at the same time[J]. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 1991, 17(5): 475–482. |

| [22] | Brunyé T T, Gagnon S A, Paczynski M, et al. Happiness by association: Breadth of free association influences affective states[J]. Cognition, 2013, 127(1): 93–98. |

| [23] | Buchholz R A, Rosenthal S B. The spirit of entrepreneurship and the qualities of moral decision making: Toward a unifying framework[J]. Journal of Business Ethics, 2005, 60(3): 307–315. |

| [24] | Bujacz A, Dunne S, Fink D, et al. Why do we enjoy creative tasks? Results from a multigroup randomized controlled study[J]. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 2016, 19: 188–197. |

| [25] | Byron K, Khazanchi S, Nazarian D. The relationship between stressors and creativity: A meta-analysis examining competing theoretical models[J]. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2010, 95(1): 201–212. |

| [26] | Caddy L, Crawford F, Page A C. “Painting a path to wellness”: Correlations between participating in a creative activity group and improved measured mental health outcome[J]. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2012, 19(4): 327–333. |

| [27] | Carnevale J B, Huang L, Vincent L C, et al. Better to give than to receive (or seek) help? The interpersonal dynamics of maintaining a reputation for creativity[J]. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 2021, 167: 144–156. |

| [28] | Carnevale J B, Vincent L C, Zhou C, et al. Beyond dishonesty: Expanding our understanding of the unexpected negative consequences of creativity[A]. Academy of management proceedings[C]. Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management, 2019. |

| [29] | Chamorro-Premuzic T. Creativity versus conscientiousness: Which is a better predictor of student performance?[J]. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 2006, 20(4): 521–531. |

| [30] | Chiu F C, Hsu C C, Lin Y N, et al. Effects of creative thinking and its personality determinants on negative emotion regulation[J]. Psychological Reports, 2019, 122(3): 916–943. |

| [31] | Conner T S, DeYoung C G, Silvia P J. Everyday creative activity as a path to flourishing[J]. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2018, 13(2): 181–189. |

| [32] | Cropley A. Creativity: A bundle of paradoxes[J]. Gifted and Talented International, 1997, 12(1): 8–14. |

| [33] | Csikszentmihalyi M, Montijo M N, Mouton A R. Flow theory: Optimizing elite performance in the creative realm[A]. Pfeiffer S I, Shaunessy-Dedrick E, Foley-Nicpon M. APA handbook of giftedness and talent[M]. Washington: American Psychological Association, 2018. |

| [34] | Dadaboyev S M U, Baek Y, Ahn S I. Victimizing innovative employees: Joint roles of in-role behavior and task interdependence[J]. International Journal of Conflict Management, 2021, 32(2): 250–265. |

| [35] | Damanpour F, Evan W M. Organizational innovation and performance: The problem of “organizational lag”[J]. Administrative Science Quarterly, 1984, 29(3): 392–409. |

| [36] | Davidovitch N, Milgram R M. Creative thinking as a predictor of teacher effectiveness in higher education[J]. Creativity Research Journal, 2006, 18(3): 385–390. |

| [37] | Elmore K C, Luna-Lucero M. Light bulbs or seeds? How metaphors for ideas influence judgments about genius[J]. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2017, 8(2): 200–208. |

| [38] | Eun H J, Chua R Y J. Gender differences in responses to organizational creativity pressure: The mediating role of P-O fit[A]. Academy of management proceedings[C]. Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management, 2020. |

| [39] | Feist G J. The affective consequences of artistic and scientific problem solving[J]. Cognition & Emotion, 1994, 8(6): 489–502. |

| [40] | Fischer R, Hommel B. Deep thinking increases task-set shielding and reduces shifting flexibility in dual-task performance[J]. Cognition, 2012, 123(2): 303–307. |

| [41] | Forgeard M J C. When, how, and for whom does creativity predict well-being?[D]. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2015. |

| [42] | Giarratana M S, Mariani M, Weller I. Rewards for patents and inventor behaviors in industrial research and development[J]. Academy of Management Journal, 2018, 61(1): 264–292. |

| [43] | Gino F, Ariely D. The dark side of creativity: Original thinkers can be more dishonest[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2012, 102(3): 445–459. |

| [44] | Goncalo J A, Katz J H. Your soul spills out: The creative act feels self-disclosing[J]. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2020, 46(5): 679–692. |

| [45] | Goncalo J A, Katz J H, Vincent L C, et al. Creativity connects: How the creative process fosters social connection and combats loneliness at work[A]. Zhou J, Rouse E D. Handbook of research on creativity and innovation[M]. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2021. |

| [46] | Goncalo J A, Vincent L C, Krause V. The liberating consequences of creative work: How a creative outlet lifts the physical burden of secrecy[J]. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2015, 59: 32–39. |

| [47] | Gutworth M B, Hunter S T. Ethical saliency: Deterring deviance in creative individuals[J]. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 2017, 11(4): 428–439. |

| [48] | Harari M B, Reaves A C, Viswesvaran C. Creative and innovative performance: A meta-analysis of relationships with task, citizenship, and counterproductive job performance dimensions[J]. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 2016, 25(4): 495–511. |

| [49] | Harrison S, Rouse E D, Amabile T M. Flipping the script: Creativity as an antecedent[A]. Academy of management proceedings[C]. Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management, 2014. |

| [50] | Harrison S H, Wagner D T. Spilling outside the box: The effects of individuals’ creative behaviors at work on time spent with their spouses at home[J]. Academy of Management Journal, 2016, 59(3): 841–859. |

| [51] | He Z L, Wong P K. Exploration vs. exploitation: An empirical test of the ambidexterity hypothesis[J]. Organization Science, 2004, 15(4): 481–494. |

| [52] | Helzer E G, Kim S H. Creativity for workplace well-being[J]. Academy of Management Perspectives, 2019, 33(2): 134–147. |

| [53] | Henderson R M, Clark K B. Architectural innovation: The reconfiguration of existing product technologies and the failure of established firms[J]. Administrative Science Quarterly, 1990, 35(1): 9–30. |

| [54] | Hora S, Badura K L, Lemoine G J, et al. A meta-analytic examination of the gender difference in creative performance[J]. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2022, 107(11): 1926–1950. |

| [55] | Hui P P, Chiu W C K, Pang E, et al. Seeing through and breaking through: The role of perspective taking in the relationship between creativity and moral reasoning[J]. Journal of Business Ethics, 2022, 180(1): 57–69. |

| [56] | Hunter S T, Cushenbery L D, Jayne B. Why dual leaders will drive innovation: Resolving the exploration and exploitation dilemma with a conservation of resources solution[J]. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2017, 38(8): 1183–1195. |

| [57] | Jamison J. Narrative means to engagement ends: Dispositional creativity’s role in moderating employee burnout[A]. Academy of management proceedings[C]. Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management, 2019. |

| [58] | Janssen O. Innovative behaviour and job involvement at the price of conflict and less satisfactory relations with co-workers[J]. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 2003, 76(3): 347–364. |

| [59] | Janssen O. How fairness perceptions make innovative behavior more or less stressful[J]. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2004, 25(2): 201–215. |

| [60] | Janssen O, van de Vliert E, West M. The bright and dark sides of individual and group innovation: A special issue introduction[J]. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2004, 25(2): 129–145. |

| [61] | Jensen K, Kovács B, Sorenson O. Gender differences in obtaining and maintaining patent rights[J]. Nature Biotechnology, 2018, 36(4): 307–309. |

| [62] | Kapoor H, Kaufman J C. Meaning-making through creativity during COVID-19[J]. Frontiers in Psychology, 2020, 11: 595990. |

| [63] | Katz J H. The cost of new ideas: Idea generators become less satisfied[J]. Academy of Management Discoveries, 2020, 6(4): 663–673. |

| [64] | Kauppila O P, Tempelaar M P. The social-cognitive underpinnings of employees’ ambidextrous behaviour and the supportive role of group managers’ leadership[J]. Journal of Management Studies, 2016, 53(6): 1019–1044. |

| [65] | Keem S, Breidenthal A, Liu D, et al. Creating alone: When and why creative performance leads to coworker aggression[R]. Paper presented at the academy of management annual meeting, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 2019. |

| [66] | Keem S, Shalley C E, Kim E, et al. Are creative individuals bad apples? A dual pathway model of unethical behavior[J]. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2018, 103(4): 416–431. |

| [67] | Khessina O M, Goncalo J A, Krause V. It’s time to sober up: The direct costs, side effects and long-term consequences of creativity and innovation[J]. Research in Organizational Behavior, 2018, 38: 107–135. |

| [68] | Krause V, Vincent L C, Goncalo J A. Fat, drunk, and lazy: How engaging in creative tasks can cause unhealthy choice[R]. Paper presented at the academy of management annual meeting, Bostion, Massachusetts, USA, 2019. |

| [69] | Lebuda I, Karwowski M, Galang A J R, et al. Personality predictors of creative achievement and lawbreaking behavior[J]. Current Psychology, 2021, 40(8): 3629–3638. |

| [70] | Leckey J. The therapeutic effectiveness of creative activities on mental well-being: A systematic review of the literature[J]. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2011, 18(6): 501–509. |

| [71] | Lengnick-Hall C A. Innovation and competitive advantage: What we know and what we need to learn[J]. Journal of Management, 1992, 18(2): 399–429. |

| [72] | Lewis M W. Exploring paradox: Toward a more comprehensive guide[J]. The Academy of Management Review, 2000, 25(4): 760–776. |

| [73] | Li C R, Yang Y Y, Lin C J, et al. The curvilinear relationship between within-person creative self-efficacy and individual creative performance: The moderating role of approach/avoidance motivations[J]. Personnel Review, 2020, 49(9): 2073–2091. |

| [74] | Li S. Gatekeeper or innovator: When do supervisors ostracize creative employees?[A]. Academy of management proceedings[C]. Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management, 2020. |

| [75] | Liu D, Chen X P, Yao X. From autonomy to creativity: A multilevel investigation of the mediating role of harmonious passion[J]. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2011, 96(2): 294–309. |

| [76] | Luksyte A, Unsworth K L, Avery D R. Innovative work behavior and sex-based stereotypes: Examining sex differences in perceptions and evaluations of innovative work behavior[J]. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2018, 39(3): 292–305. |

| [77] | Mai K M, Ellis A P J, Welsh D T. The gray side of creativity: Exploring the role of activation in the link between creative personality and unethical behavior[J]. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2015, 60: 76–85. |

| [78] | Mai K M, Welsh D T, Wang F X, et al. Supporting creativity or creative unethicality? Empowering leadership and the role of performance pressure[J]. Journal of Business Ethics, 2022, 179(1): 111–131. |

| [79] | Mao Y N, He J, Yang D T. The dark sides of engaging in creative processes: Coworker envy, workplace ostracism, and incivility[J]. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 2021, 38(4): 1261–1281. |

| [80] | Martin C L, Ruble D N. Patterns of gender development[J]. Annual Review of Psychology, 2010, 61: 353–381. |

| [81] | McNiff S. Art heals: How creativity cures the soul[M]. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2004. |

| [82] | Ming X D, Bai X W. An ego depletion perspective of how and when creative engagement engenders unethical behavior[A]. Academy of management proceedings[C]. Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management, 2021. |

| [83] | Miron E, Erez M, Naveh E. Do personal characteristics and cultural values that promote innovation, quality, and efficiency compete or complement each other?[J]. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2004, 25(2): 175–199. |

| [84] | Miron-Spektor E, Beenen G. Motivating creativity: The effects of sequential and simultaneous learning and performance achievement goals on product novelty and usefulness[J]. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 2015, 127: 53–65. |

| [85] | Miron-Spektor E, Erez M. Looking at creativity through a paradox lens: Deeper understanding and new insights[A]. Smith W K, Lewis M W, Jarzabkowski P, et al. The oxford handbook of organizational paradox[M]. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. |

| [86] | Miron-Spektor E, Ingram A, Keller J, et al. Microfoundations of organizational paradox: The problem is how we think about the problem[J]. Academy of Management Journal, 2018, 61(1): 26–45. |

| [87] | Miron-Spektor E, Vashdi D R, Gopher H. Bright sparks and enquiring minds: Differential effects of goal orientation on the creativity trajectory[J]. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2022, 107(2): 310–318. |

| [88] | Mueller J S, Goncalo J A, Kamdar D. Recognizing creative leadership: Can creative idea expression negatively relate to perceptions of leadership potential?[J]. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2011, 47(2): 494–498. |

| [89] | Mumford M D, Waples E P, Antes A L, et al. Creativity and ethics: The relationship of creative and ethical problem-solving[J]. Creativity Research Journal, 2010, 22(1): 74–89. |

| [90] | Ng T W H, Wang M. An actor–partner interdependence model of employees’ and coworkers’ innovative behavior, psychological detachment, and strain reactions[J]. Personnel Psychology, 2019, 72(3): 445–476. |

| [91] | Ng T W H, Yam K C. When and why does employee creativity fuel deviance? Key psychological mechanisms[J]. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2019, 104(9): 1144–1163. |

| [92] | Niedenthal P M, Barsalou L W, Winkielman P, et al. Embodiment in attitudes, social perception, and emotion[J]. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2005, 9(3): 184–211. |

| [93] | Papachroni A, Heracleous L. Ambidexterity as practice: Individual ambidexterity through paradoxical practices[J]. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 2020, 56(2): 143–165. |

| [94] | Proudfoot D. The perceived association between agentic traits and creativity: Implications for gender bias and creativity evaluation[D]. Durham: Duke University, 2017. |

| [95] | Proudfoot D, Kay A C, Koval C Z. A gender bias in the attribution of creativity: Archival and experimental evidence for the perceived association between masculinity and creative thinking[J]. Psychological Science, 2015, 26(11): 1751–1761. |

| [96] | Qin X, Dust S B, DiRenzo M S, et al. Negative creativity in leader-follower relations: A daily investigation of leaders’ creative mindset, moral disengagement, and abusive supervision[J]. Journal of Business and Psychology, 2020, 35(5): 665–682. |

| [97] | Qin X, Shepherd D A, Lin D M, et al. The dark side of entrepreneurs’ creativity: Investigating how and when entrepreneurs’ creativity increases the favorability of potential opportunities that harm nature[J]. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 2022, 46(4): 857–883. |

| [98] | Raisch S, Birkinshaw J, Probst G, et al. Organizational ambidexterity: Balancing exploitation and exploration for sustained performance[J]. Organization Science, 2009, 20(4): 685–695. |

| [99] | Rhodes M. An analysis of creativity[J]. The Phi Delta Kappan, 1961, 42(7): 305–310. |

| [100] | Rogan M, Mors M L. A network perspective on individual-level ambidexterity in organizations[J]. Organization Science, 2014, 25(6): 1860–1877. |

| [101] | Rosing K, Bledow R, Frese M, et al. The temporal pattern of creativity and implementation in teams[J]. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 2018, 91(4): 798–822. |

| [102] | Rouse E D. Where you end and I begin: Understanding intimate co-creation[J]. Academy of Management Review, 2020, 45(1): 181–204. |

| [103] | Sarooghi H, Libaers D, Burkemper A. Examining the relationship between creativity and innovation: A meta-analysis of organizational, cultural, and environmental factors[J]. Journal of Business Venturing, 2015, 30(5): 714–731. |

| [104] | Schad J, Lewis M W, Raisch S, et al. Paradox research in management science: Looking back to move forward[J]. Academy of Management Annals, 2016, 10(1): 5–64. |

| [105] | Schilling M A. Quirky: The remarkable story of the traits, foibles, and genius of breakthrough innovators who changed the world[M]. Birmingham: Public Affairs, 2018. |

| [106] | Ścigała K A, Schild C, Zettler I. Doing justice to creative justifications: Creativity, honesty-humility, and (un)ethical justifications[J]. Journal of Research in Personality, 2020, 89(6): 104033. |

| [107] | Shao Y, Nijstad B A, Täuber S. Creativity under workload pressure and integrative complexity: The double-edged sword of paradoxical leadership[J]. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 2019, 155: 7–19. |

| [108] | Shen W B, Yuan Y, Yi B S, et al. A theoretical and critical examination on the relationship between creativity and morality[J]. Current Psychology, 2019, 38(2): 469–485. |

| [109] | Smith W K, Lewis M W. Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing[J]. The Academy of Management Review, 2011, 36(2): 381–403. |

| [110] | Storme M, Celik P, Myszkowski N. Creativity and unethicality: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 2021, 15(4): 664–672. |

| [111] | Sue-Chan C, Hempel P S. The creativity-performance relationship: How rewarding creativity moderates the expression of creativity[J]. Human Resource Management, 2016, 55(4): 637–653. |

| [112] | Tang M, Hofreiter S, Reiter-Palmon R, et al. Creativity as a means to well-being in times of COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a cross-cultural study[J]. Frontiers in Psychology, 2021, 12: 601389. |

| [113] | Teal E J, Carroll A B. Moral reasoning skills: Are entrepreneurs different?[J]. Journal of Business Ethics, 1999, 19(3): 229–240. |

| [114] | Tempelaar M P, Rosenkranz N A. Switching hats: The effect of role transition on individual ambidexterity[J]. Journal of Management, 2019, 45(4): 1517–1539. |

| [115] | Umphress E E, Gardner R G, Stoverink A C, et al. Feeling activated and acting unethically: The influence of activated mood on unethical behavior to benefit a teammate[J]. Personnel Psychology, 2020, 73(1): 95–123. |

| [116] | Vincent L C, Kouchaki M. Creative, rare, entitled, and dishonest: How commonality of creativity in one’s group decreases an individual’s entitlement and dishonesty[J]. Academy of Management Journal, 2016, 59(4): 1451–1473. |

| [117] | Vuori T O, Huy Q N. Distributed attention and shared emotions in the innovation process: How Nokia lost the smartphone battle[J]. Administrative Science Quarterly, 2016, 61(1): 9–51. |

| [118] | Walczyk J J, Runco M A, Tripp S M, et al. The creativity of lying: Divergent thinking and ideational correlates of the resolution of social dilemmas[J]. Creativity Research Journal, 2008, 20(3): 328–342. |

| [119] | Weitzel U, Urbig D, Desai S, et al. The good, the bad, and the talented: Entrepreneurial talent and selfish behavior[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 2010, 76(1): 64–81. |

| [120] | Wronska M K, Kolańczyk A, Nijstad B A. Engaging in creativity broadens attentional scope[J]. Frontiers in Psychology, 2018, 9: 1772. |

| [121] | Wu S Q, Yuan Y J. Role differentiation in creative processes: A configural approach to team creativity[A]. Academy of management proceedings[C]. Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management, 2020. |

| [122] | Xu L D, Mehta R, Dahl D W. Leveraging creativity in charity marketing: The impact of engaging in creative activities on subsequent donation behavior[J]. Journal of Marketing, 2022, 86(5): 79–94. |

| [123] | Zacher H, Robinson A J, Rosing K. Ambidextrous leadership and employees’ self-reported innovative performance: The role of exploration and exploitation behaviors[J]. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 2016, 50(1): 24–46. |

| [124] | Zhang G X, Chan A, Zhong J N, et al. Creativity and social alienation: The costs of being creative[J]. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 2016, 27(12): 1252–1276. |

| [125] | Zhang X M, Bartol K M. The influence of creative process engagement on employee creative performance and overall job performance: A curvilinear assessment[J]. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2010, 95(5): 862–873. |

| [126] | Zhang Y, Han Y L. Paradoxical leader behavior in long-term corporate development: Antecedents and consequences[J]. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 2019, 155: 42–54. |

| [127] | Zhang Y, Li J J, Song Y H, et al. Radical and incremental creativity profiles: Associations with work performance and well-being[A]. Academy of management proceedings[C]. Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management, 2020. |

| [128] | Zhang Y, Zhang J, Forest J, et al. The negative and positive aspects of employees’ innovative behavior: Role of goals of employees and supervisors[J]. Frontiers in Psychology, 2018, 9: 1871. |

| [129] | Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Law K S, et al. Paradoxical leadership, subjective ambivalence, and employee creativity: Effects of employee holistic thinking[J]. Journal of Management Studies, 2022, 59(3): 695–723. |

| [130] | Zheng X M, Qin X, Liu X, et al. Will creative employees always make trouble? Investigating the roles of moral identity and moral disengagement[J]. Journal of Business Ethics, 2019, 157(3): 653–672. |

| [131] | Zhou J, Oldham G R, Chuang A, et al. Enhancing employee creativity: Effects of choice, rewards and personality[J]. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2022, 107(3): 503–513. |